In this Module

Chapter 1

Timelines

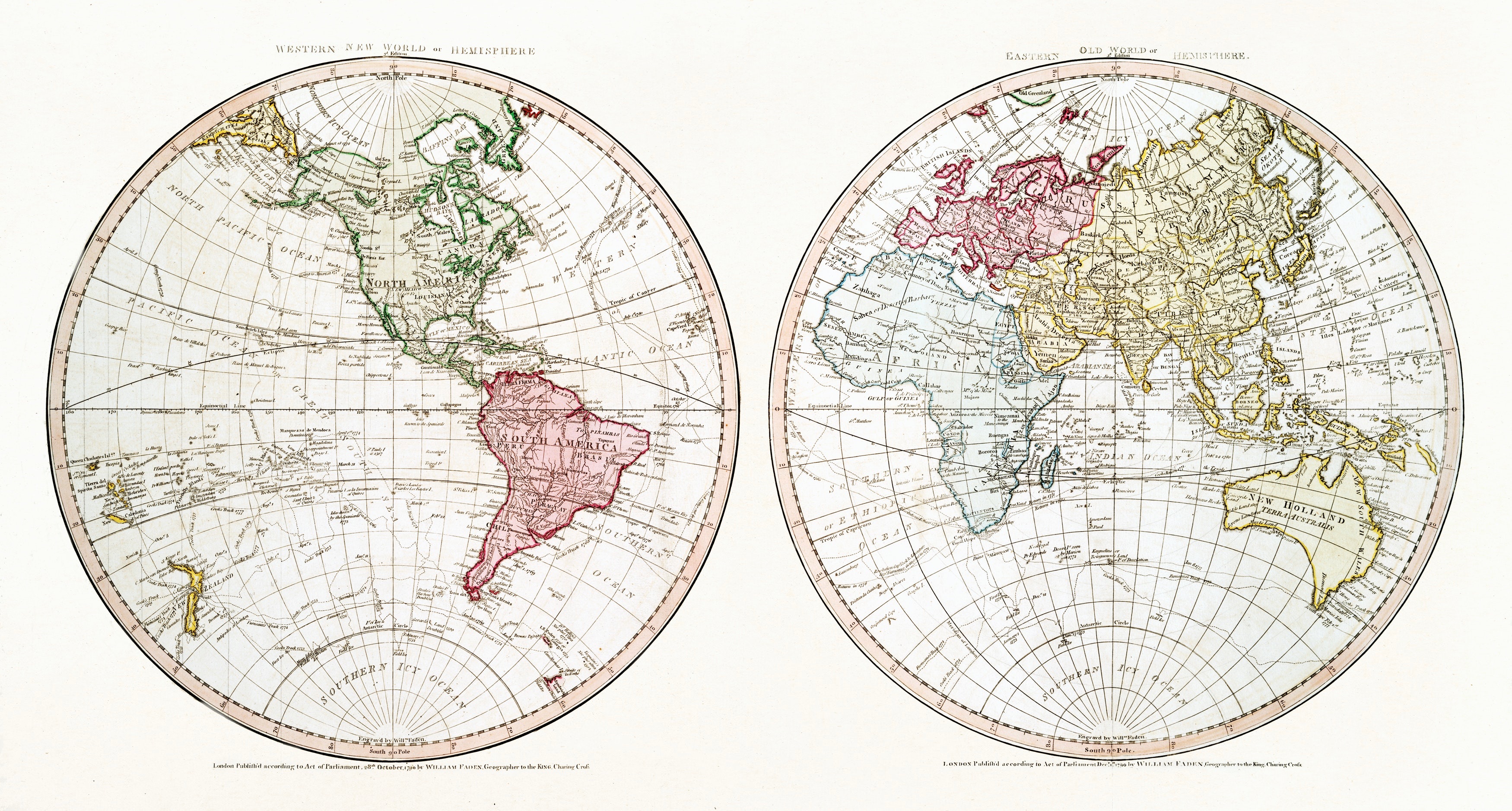

Indigenous peoples in North America have complex histories that precede and overlap European contact and colonization. Each First Nation, Inuit and Métis community has an experience that is unique to them.

“Education will lead to understanding; understanding will lead to action. Education and understanding are going to be key to moving us forward.”

-National Chief Perry Bellegarde

As you read and research through these various documents and resources, be mindful of whose lens the material is being presented through. Are Indigenous stories and experiences conveyed with integrity and respect? Are individuals and communities portrayed in a balanced manner as full participants in their own lives, complete with a full range of human emotion and experience?

Timelines

Indigenous peoples in North America have complex histories that precede and overlap European contact and colonization. Each First Nation, Inuit and Métis community has an experience that is unique to them.

The purpose of these timelines is to provide a graphic representation of the achievements, conflicts and key points in Indigenous peoples’ histories.

A timeline helps students to understand the historical experiences of Indigenous peoples, and to inform the present. These timelines highlight the collective experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit, their encounters with colonization and colonialism, their existence since time immemorial and their ongoing resilience.

Certain timelines follow a pre-contact history, using archaeological and anthropological research; however, many First Nations use oral history and storytelling to explain their history. These timelines, therefore, are generalized and should be used to create an understanding of a broad, collective history. These are great places to begin.

National Timelines: Common Shared Histories from Throughout Canada

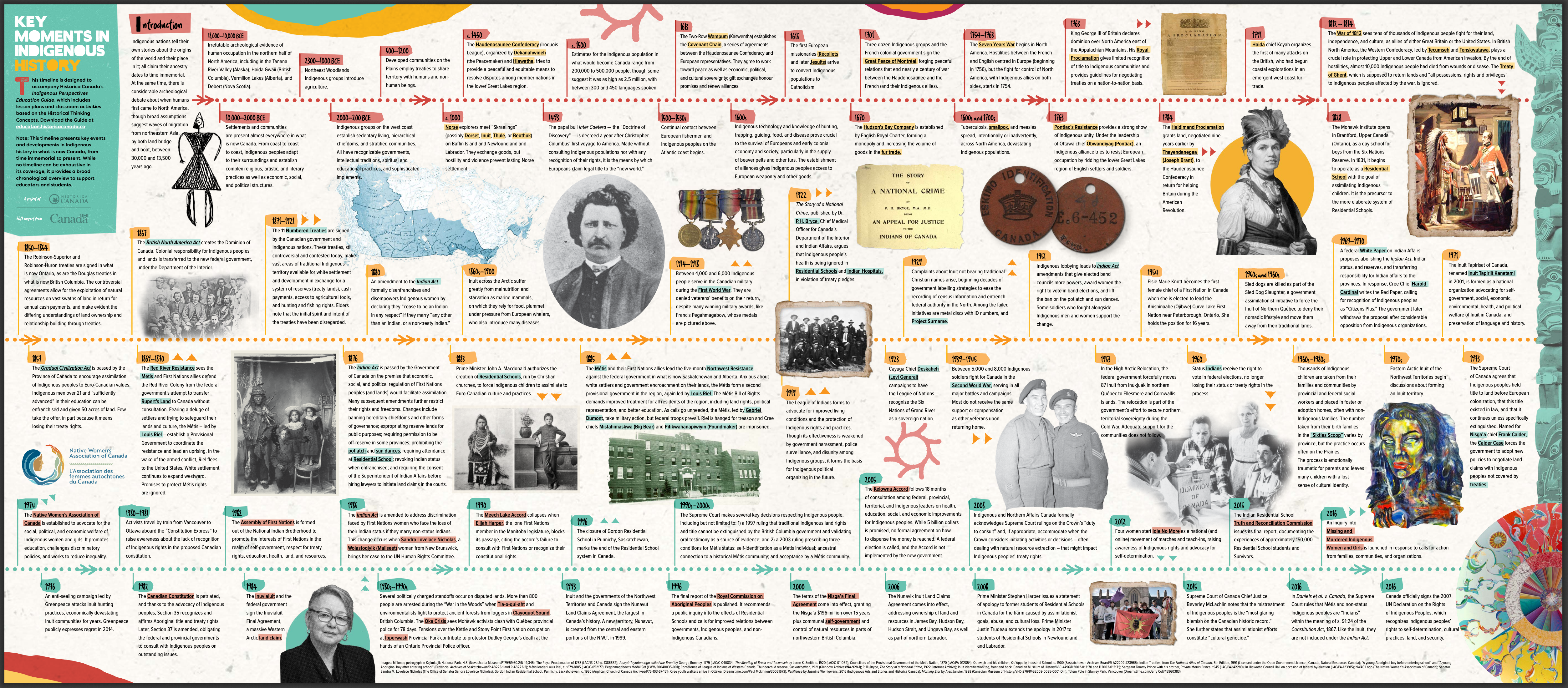

Key Moments in Indigenous History

Historica Canada

Though not exhaustive, Historica Canada presents a well-rounded history of this land. It explains the cultural ties that Indigenous nations have had to this land since time immemorial. Through an Indigenous lens, the timeline presents archaeological data and historical events that demonstrate First Nations and Canada’s shared history.

Timeline of First Nations Self-Governance

National Centre for First Nations Governance

This document provides a timeline of First Nations Self-Governance. It begins with pre-contact organization and traditional governance. It then follows with the history of Treaties, colonial influence through Confederation and the Indian Act, and contemporary self-governance.

History of Residential Schools in Canada

National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation

This timeline presents an outline of the historical, legal and political proceedings of Indian Residential Schools in Canada. It includes mention of the Indian Act’s introduction and its amendments.

The Indian Act Timeline

-

1857: The Gradual Civilization Act

An act to encourage the gradual civilization of Indian Tribes through compulsory enfranchisement. The Act denotes that any First Nations male who was free of debt, literate and of good moral character could be awarded full ownership of 59 acres of reserve land. However, he would then be considered enfranchised, cease to be an Indian and cut all ties to his band.

-

1869: The Gradual Enfranchisement Act

An act for the gradual enfranchisement of Indians and the management of Indian affairs, and to include changes to the enfranchisement process. The Act increased government control of on-reserve political systems through the Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs who determined when and how First Nations elections of governance would take place. The Canadian Government replaced traditional forms of choosing First Nations leadership with the voting system for Chief and Council to take place every two years.

-

1876: The Indian Act

An “Act to amend and consolidate the laws respecting Indians,” the original Indian Act, was passed. The Indian Act was not part of any treaty made between First Nations peoples and the British Crown. The sole purpose of the act was to assimilate and colonize First Nations peoples.

-

1879: Amendments to Indian Act

“An Act to amend ‘The Indian Act, 1876′” amended the act to: allow “half-breeds” to withdraw from Treaty; to allow punishment for trespassing on reserves; to expand the powers of Chief and Council to include punishment by fine, penalty or imprisonment; and to prohibit houses of prostitution.

-

1881: Department of Indian Affairs

Indian Act amended to make officers of the Department of Indian Affairs, including Indian Agents, legal justices of the peace, able to enforce regulations under act. The following year they were granted the same legal power as magistrates. Further amended to prohibit the sale of agricultural produce by Indians in Prairie Provinces without an appropriate permit from an Indian agent. This prohibition is still included in the Indian Act, though it is not enforced.

-

1884: Prohibiting Spiritual Ceremonies

Amended to prevent elected band leaders who have been deposed from office from being re-elected. Further amended to prohibit First Nations peoples from conducting or participating in spiritual ceremonies such as the potlatch and Tamanawas dances.

-

1894: Compulsory Schooling

Act amended to force attendance of Indian youth in school. Industrial schools ran from 1883-1923. After 1923 these schools became known as “residential schools.” Part of the federal government assimilation policy focused on eliminating First Nations children’s cultural beliefs and practices. First Nations parents were fined or jailed if they did not send their children to residential schools.

-

1905: Forced Removal

Amended to allow First Nations people to be removed from reserves near towns with more than 8,000 residents.

-

1911: Oliver Act

Amended to allow municipalities and companies to expropriate portions of reserves. Further amended to allow a judge to move an entire reserve away from a municipality. These amendments were also known as the Oliver Act.

-

1914: Amendments for Western Indians

Amended to require western Indians to seek official permission before appearing in “Aboriginal costume” during any “dance, show, exhibition, stampede or pageant.”

-

1918: Leasing Reserve Land to Non-Aboriginals

Amended to allow the Superintendent-General to lease out uncultivated reserve lands to non-Aboriginals if it was to be used for farming or pasture.

-

1920: Residential Schools

Amended to make it mandatory for Aboriginal parents to send their children to Indian residential school. Further amended to allow for the involuntary enfranchisement (and loss of treaty rights) of any status Indian considered fit by the Department of Indian Affairs, without the possession of land previously required for those living off reserve. This amendment was repealed two years later but reintroduced in a modified form in 1933.

-

1927: Impact of Land Claims

Amended to prevent anyone (Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal) from soliciting funds for Indian legal claims unless they secured a special license from the Superintendent-General. This prevented any First Nation from pursuing Aboriginal land claims.

-

1936: Impositions on Band Council Meeting

Amended to allow Indian agents to direct band council meetings, and to cast a deciding vote in the event of a tie.

-

1951: Removal of Provisions

The 1951 amendments removed some of the provisions in the legislation, including the banning of spiritual dances and ceremonies, the sale and slaughter of livestock, and the prohibition on pursuing claims against the government. First Nations peoples were now permitted to hire lawyers to represent them in legal matters, and status women were now able to vote in band elections.

Further amendments allowed for the compulsory enfranchisement of First Nations women who married non-status men (including Métis, Inuit and non-status Indian, as well as non-Aboriginal men), thus causing them to lose their status, and denying Indian status to any children from the marriage.

-

1985: Bill C-31

Bill C-31 was introduced to void the enfranchisement process, which allowed status Indian women the right to keep or regain their status even after “marrying out” and to grant status to the children (but not grandchildren) of such a marriage. Under this amendment, full status Indians are referred to as 6–1. A child of a marriage between a status (6–1) person and a non-status person qualifies for 6–2 (half) status. If that child grows up and in turn married a non-status person, the child of that union would be non-status. If a 6–2 marries a 6–1 or another 6–2, the children revert to 6–1 status. Blood quantum is disregarded, or rather, replaced with a “two generation cut-off clause”. It was estimated that approximately half of status Indians were married to non-status people, meaning Bill C-31 legislation would complete legal assimilation in a matter of a few generations.

-

2000: Voting Off-Reserve

Amended to allow band members living off reserves to vote in band elections and referendums.

-

2011: Bill C-3

Bill C-3 was introduced that amended provisions that were found unconstitutional. These amendments ensured that eligible grandchildren of women who lost status as a result of marrying non-status men became entitled to registration (Indian status). As a result of this legislation approximately 45,000 persons became newly entitled to registration.

-

2013: Métis and Non-Status Indians

Amendments to include 200,000 Métis and 400,000 non-status Indians in the federal responsibility for Indians after a 13-year legal dispute.

-

2016: Daniels v. Canada

In 2016 the Supreme Court of Canada ruled on Daniels v. Canada or the ‘Daniels Decision’. The Daniels decision stated that Metis and non-status Indians are considered under the term ‘Indian’ under section 91 (24) of the Constitution Act, 186. The Daniels decision does not provide Metis or non-Status First Nations status under the Indian Act.

-

2017: Bill S-3

Bill S-3, Act to amend the Indian Act in response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in Descheneaux c. Canada (Procureur général).

Timeline on Residential Schools and Education in Canada

wherearethechildren.ca

This timeline presents an overview of the history of Residential Schools in Canada.

Timeline on Indigenous Suffrage

The Canadian Encyclopedia

This timeline follows Suffrage “(the right to vote) for Indigenous peoples across Canada. Provincial agreements occurred separate from a federal decision to allow Indigenous people to vote in elections without enfranchisement. This timeline also includes First Nations people’s involvement in political positions.

History of Treaties in Canada

Historica Canada

This education guide provides an overview of Treaty making, and their historical and ongoing importance. It also includes learning activities for educators.

Regional Timelines: A Sample From Regions Throughout Canada

Indigenous Historical Timeline in British Columbia

Union of BC Indian Chiefs

This expansive historical timeline outlines historical events in Canada from the 1700s to present day.

Timeline History of Aboriginal Peoples in British Columbia

BC Teacher’s Federation

The BC Teacher’s Federation presents selected events important to the history of Indigenous peoples in British Columbia.

Timeline of Indigenous History in Alberta

Alberta Teachers Association

This timeline follows Indigenous nations living in what is now Alberta from pre-Confederation to the 2016.

Treaties Timeline

Some of Canada’s modern Treaties/Comprehensive Land Claims and Self Government Agreements.

-

1975

– James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and Complementary Agreements (effective date 1977)

-

1978

– The Northeastern Quebec Agreement

– Labrador Innu Nation Final Agreement

-

1979

– Quebec Innu-Regroupement Petapan Inc Final Agreement

-

1984

– The Western Arctic Inuvialuit Final Agreement

-

1986

– Sechelt Indian Band Self-Government Agreement

-

1991

– Meadow Lake Final Agreement

-

1992

– The Gwich’in (Dene/Métis) Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement

-

1993

– Nunavut Land Claims Agreement

– Sahtu Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement – Volume I

– Sahtu Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement – Volume II

– Umbrella Final Agreement between the Government of Canada, the Council for Yukon Indians and the Government of the Yukon

– Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation Final Agreement (effective date 1995)

– Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation Self-Government Agreement (effective date 1995)

– Champagne and Aishihik First Nations Final Agreement (effective date 1995)

– Champagne and Aishihik First Nations Self-Government Agreement (effective date 1995)

– Teslin Tlingit Council Final Agreement (effective date 1995)

– Teslin Tlingit Council Self-Government Agreement (effective date 1995)

– Nacho Nyak Dun First Nation Final Agreement (effective date 1995)

– Nacho Nyak Dun First Nation Self-Government Agreement/ (effective date 1995)

– Nunavut Land Claims Agreement

-

1994

– Lheidli T’enneh Final Agreement

– Sechelt Final Agreement

-

1995

– Yekooche Final Agreement

– Fort Frances Chiefs Secretariat Final Agreement

-

1996

– Deline-Sahtu Dene and Metis Final Agreement

-

1997

– Anishinabek Nation (Union of Ontario Indians) Final Agreement

– Little Salmon/Carmacks Final Agreement

– Little Salmon/Carmacks Self-Government Agreement

– Selkirk First Nation Final Agreement

– Selkirk First Nation Self Government Agreement

-

1998

-Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Final Agreement

– Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Self-Government Agreement

-

1999

– Mohawks of Akwesasne Final Agreement

– Nisga’a Final Agreement

– Manitoba Denesuline Negotiations North of 60 Final Agreement

-

2000

– Athabasca Densuline Negotiations North of 60 Final Agreement

-

2002

– In-SHUCK-ch Final Agreement

– Ta’an Kwach’an First Nation Final Agreement

– Tlicho Agreement (signed on August 25, 2003)

-

2003

– Kluane First Nation Final Agreement

– Westbank First Nation Self-Government Agreement

-

2004

– Miawpukek First Nation of Conne River Final Agreement

-

2006

– First Nation Education Steering Committee Final Agreement

– Labrador Inuit Land Claim Agreement

– Carcross/Tagish First Nation Final Agreement

– Kwanlin Dun First Nation Final Agreement

-

2007

– K’omoks First Nation Final Agreement

-

2008

– Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement

– Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement

-

2010

– Inuit Transboundary Negotiations in Northern Manitoba Final Agreement

-

2011

– Maa-nulth First Nations Final Agreement

-

2012

– Eeyou Marine Region Land Claims Final Agreement

-

2014

– Sioux Valley Dakota Nation Agreement

-

2015

– Deline First Nation Final Agreement