In this Module

Introduction to the Indian Act

The Indian Act has been described, justifiably, as archaic, outdated, colonial, racist, paternalist, and repressive. Shockingly, it is still in effect today.

“[The Indian Act] has… deprived us of our independence, our dignity, our self-respect and our responsibility.”

—Kaherine June Delisle, Kanien’kehaka First Nation Kahnawake, Quebec

Historically, control over First Nations was a British responsibility that passed to Canada after Confederation. As the fur trade ended, First Nations peoples were increasingly seen as a barrier to government plans for the settlement of western Canada. The Government called it “the Indian problem”. The Government responded to this “problem” by creating the Indian Act in 1876. The Indian Act is a legal document and a set of laws that gave the Government complete control over the lives of Indian peoples.

A famous statement in 1920 by Duncan Campbell Scott, poet, essayist, and Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, stated the prevailing attitude of his day:

Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question, and no Indian department.

There were two objectives

The Indian Act regulates and administers the lives of registered Indians and reserve communities. It imposes imperial political control and enforces restrictions on First Nations movement, their right to live where they please, and their right to practice their culture and traditions.

“The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominion as speedily as they are fit to change.”

—Sir John A. McDonald, 1887

The Gradual Civilization Act passed in 1857 and sought to assimilate each Indian into Canadian settler society through enfranchisement. Historically, if a First Nations individual wanted to vote or attend post-secondary school, they would have to renounce their Status. The purpose of assimilation was to absorb First Nations people into Canadian society.

The Indian Act built upon this notion of assimilation, forcing First Nations to give up their culture and languages. This Act also introduced the elective band council system, that emulates colonial democracy. This system still exists in First Nations governance today.

The Indian Act Timeline

-

1857: The Gradual Civilization Act

An act to encourage the gradual civilization of Indian Tribes through compulsory enfranchisement. The Act denotes that any First Nations male who was free of debt, literate and of good moral character could be awarded full ownership of 59 acres of reserve land. However, he would then be considered enfranchised, cease to be an Indian and cut all ties to his band.

-

1869: The Gradual Enfranchisement Act

An act for the gradual enfranchisement of Indians and the management of Indian affairs, and to include changes to the enfranchisement process. The Act increased government control of on-reserve political systems through the Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs who determined when and how First Nations elections of governance would take place. The Canadian Government replaced tradition forms of choosing First Nations leadership with the voting system for Chief and Council to take place every two years.

-

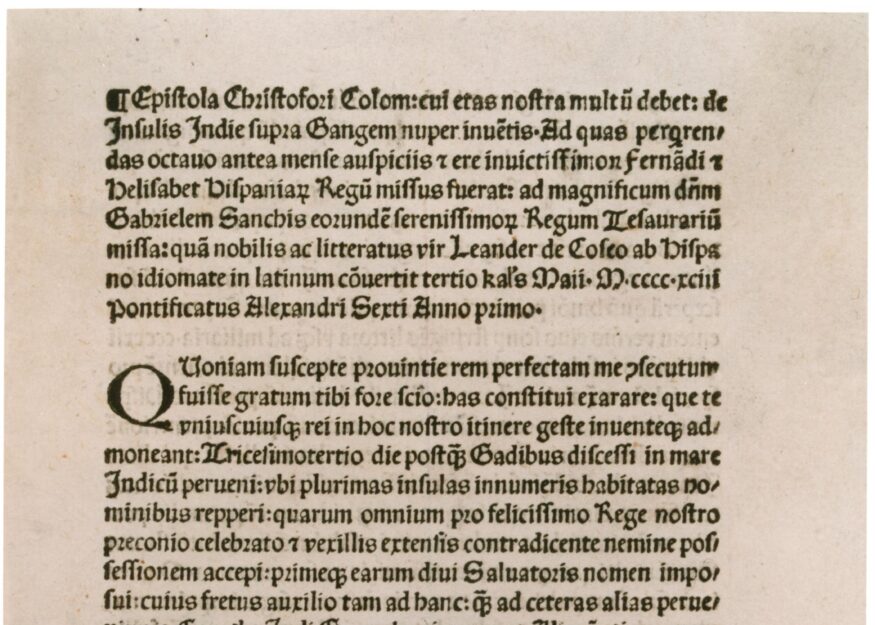

1876: The Indian Act

“An “Act to amend and consolidate the laws respecting Indians,” the original Indian Act, was passed. The Indian Act was not part of any treaty made between First Nations peoples and the British Crown. The sole purpose of the act was to assimilate and colonize First Nations peoples.

-

1879: Amendments to Indian Act

“An Act to amend ‘The Indian Act, 1876′” amended the act to: allow “half-breeds” to withdraw from Treaty; to allow punishment for trespassing on reserves; to expand the powers of Chief and Council to include punishment by fine, penalty or imprisonment; and to prohibit houses of prostitution.

-

1881: Department of Indian Affairs

Indian Act amended to make officers of the Department of Indian Affairs, including Indian Agents, legal justices of the peace, able to enforce regulations under act. The following year they were granted the same legal power as magistrates. Further amended to prohibit the sale of agricultural produce by Indians in Prairie Provinces without an appropriate permit from an Indian agent. This prohibition is still included in the Indian Act, though it is not enforced.

-

1884: Prohibiting Spiritual Ceremonies

Amended to prevent elected band leaders who have been deposed from office from being re-elected. Further amended to prohibit First Nations peoples from conducting or participating in spiritual ceremonies such as the potlatch and Tamanawas dances.

-

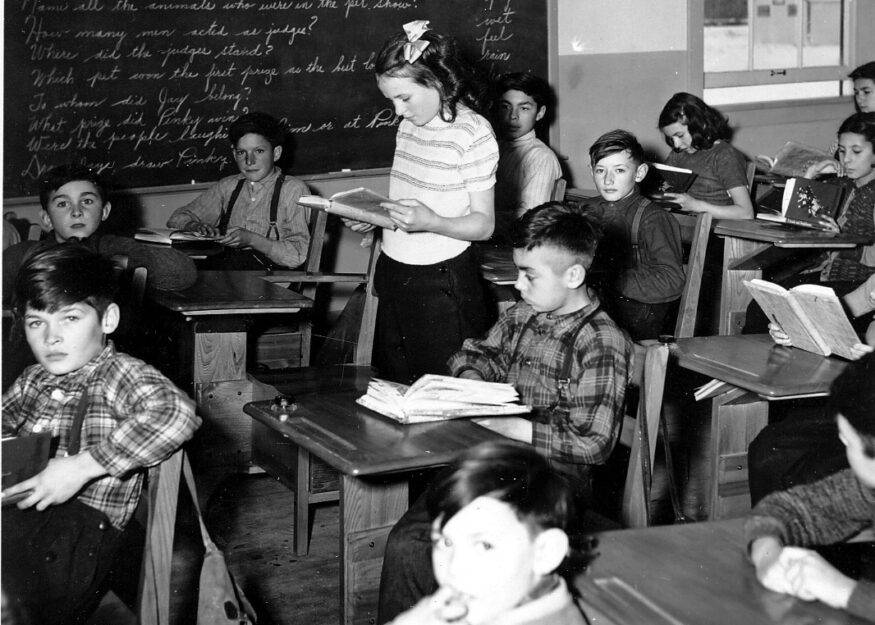

1894: Compulsory Schooling

Act amended to force attendance of Indian youth in school. Industrial schools ran from 1883-1923. After 1923 these schools became known as “residential schools.” Part of the federal government assimilation policy focused on eliminating First Nations children’s cultural beliefs and practices. First Nations parents were fined or jailed if they did not send their children to residential schools.

-

1905: Forced Removal

Amended to allow First Nations people to be removed from reserves near towns with more than 8,000 residents.

-

1911: Oliver Act

Amended to allow municipalities and companies to expropriate portions of reserves. Further amended to allow a judge to move an entire reserve away from a municipality. These amendments were also known as the Oliver Act.

-

1914: Amendments for Western Indians

Amended to require western Indians to seek official permission before appearing in “Aboriginal costume” during any “dance, show, exhibition, stampede or pageant.”

-

1918: Leasing Reserve Land to Non-Aboriginals

Amended to allow the Superintendent-General to lease out uncultivated reserve lands to non-Aboriginals if it was to be used for farming or pasture.

-

1920: Residential Schools

Amended to make it mandatory for Aboriginal parents to send their children to Indian residential school. Further amended to allow for the involuntary enfranchisement (and loss of treaty rights) of any status Indian considered fit by the Department of Indian Affairs, without the possession of land previously required for those living off reserve. This amendment was repealed two years later but reintroduced in a modified form in 1933.

-

1927: Impact of Land Claims

Amended to prevent anyone (Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal) from soliciting funds for Indian legal claims unless they secured a special license from the Superintendent-General. This prevented any First Nation from pursuing Aboriginal land claims.

-

1936: Impositions on Band Council Meetings

Amended to allow Indian agents to direct band council meetings, and to cast a deciding vote in the event of a tie.

-

1951: Removal of Provisions

The 1951 amendments removed some of the provisions in the legislation, including the banning of spiritual dances and ceremonies, the sale and slaughter of livestock, and the prohibition on pursuing claims against the government. First Nations peoples were now permitted to hire lawyers to represent them in legal matters, and status women were now able to vote in band elections. Further amendments allowed for the compulsory enfranchisement of First Nations women who married non-status men (including Métis, Inuit and non-status Indian, as well as non-Aboriginal men), thus causing them to lose their status, and denying Indian status to any children from the marriage.

-

1985: Bill C-31

Bill C-31 was introduced to void the enfranchisement process, which allowed status Indian women the right to keep or regain their status even after “marrying out” and to grant status to the children (but not grandchildren) of such a marriage. Under this amendment, full status Indians are referred to as 6–1. A child of a marriage between a status (6–1) person and a non-status person qualifies for 6–2 (half) status. If that child grows up and in turn married a non-status person, the child of that union would be non-status. If a 6–2 marries a 6–1 or another 6–2, the children revert to 6–1 status. Blood quantum is disregarded, or rather, replaced with a “two generation cut-off clause”. It was estimated that approximately half of status Indians were married to non-status people, meaning Bill C-31 legislation would complete legal assimilation in a matter of a few generations.

-

2000: Voting Off-Reserve

Amended to allow band members living off reserves to vote in band elections and referendums.

-

2011: Bill C-3

Bill C-3 was introduced that amended provisions that were found unconstitutional. These amendments ensured that eligible grandchildren of women who lost status as a result of marrying non-status men became entitled to registration (Indian status). As a result of this legislation approximately 45,000 persons became newly entitled to registration.

-

2013: Métis and Non-Status Indians

Amendments to include 200,000 Métis and 400,000 non-status Indians in the federal responsibility for Indians after a 13-year legal dispute.

-

2016: Daniels v. Canada

In 2016 the Supreme Court of Canada ruled on Daniels v. Canada or the ‘Daniels Decision’. The Daniels decision stated that Metis and non-status Indians are considered under the term ‘Indian’ under section 91 (24) of the Constitution Act, 186. The Daniels decision does not provide Metis or non-Status First Nations status under the Indian Act.

-

2017: Bill S-3

Bill S-3, Act to amend the Indian Act in response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in Descheneaux c. Canada (Procureur général).