In this Module

What are Residential Schools?

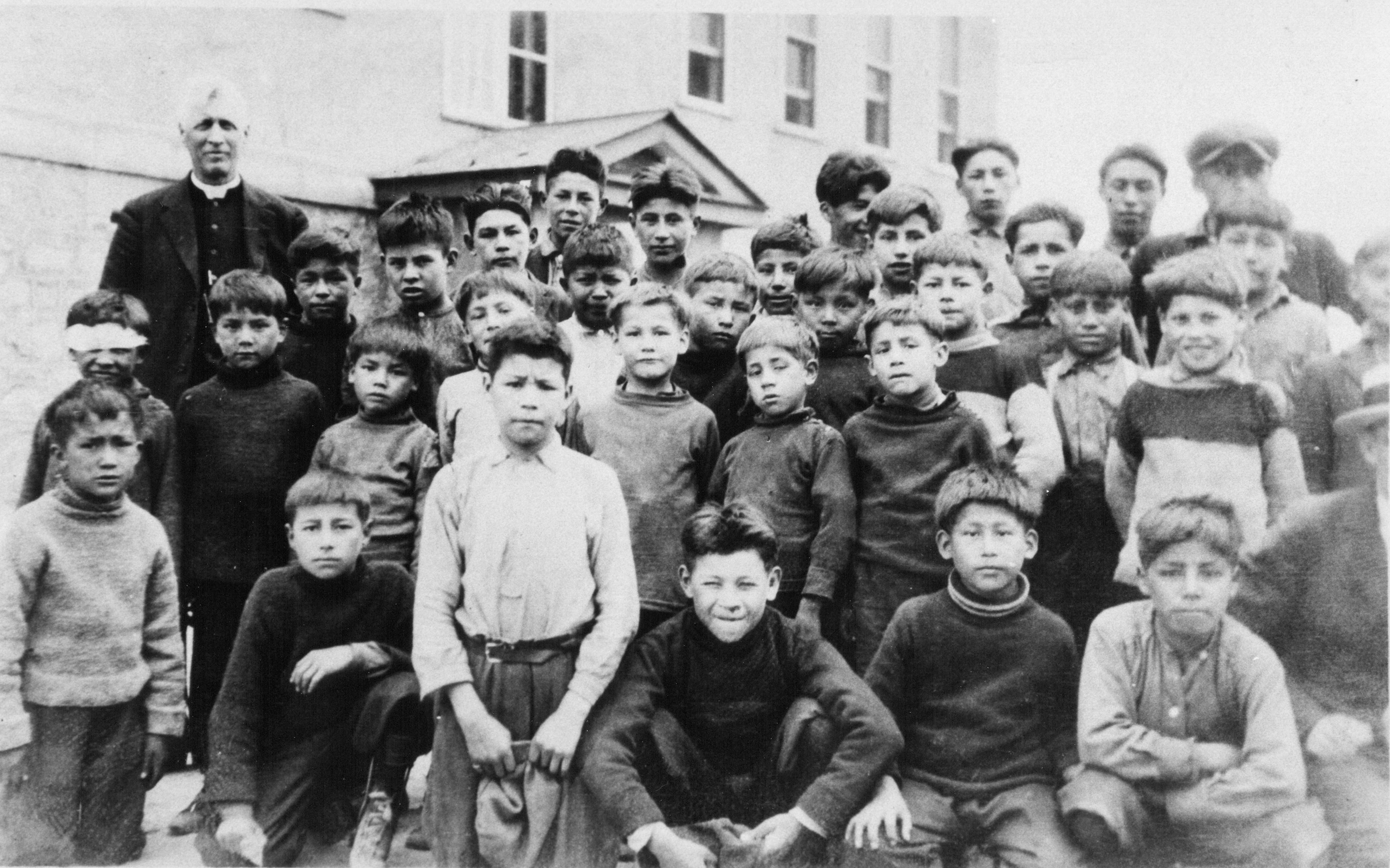

Residential schools were boarding schools for Indigenous (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) children and youth, financed by the federal government but staffed and run by several Christian religious institutions— the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian, United and Methodist Churches. Children were separated from their families and communities, sometimes by force, and lived in and attended classes at the schools for most of the year. Often the residential schools were located far from the students’ home communities.

How long did residential schools exist

From their start in the 1800s until the last one closed in 1996, about 130 residential schools operated in every province and territory in Canada, except for the provinces of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. During this period, over 150,000 Indigenous youth were enrolled in residential schools. Enrollment reached a peak about 1930, with over 17,000 students in 80 schools. As of 2012, about 93,000 Indigenous adults who attended residential schools were still alive to tell their stories and describe their experiences.

-

1620-1680

Boarding schools are established for Indian youth by the Récollets, a French order in New France, and later the Jesuits and the female order the Ursulines. This form of schooling lasts until the 1680s

-

1820

Early church schools are run by Protestants, Catholics, Anglicans and Methodists

-

1847

Egerton Ryerson produces a study of native education at the request of the assistant superintendent general of Infian affairs. His findings become the model for future Indian residential schools. Ryerson recommends that domestic education and religious instruction is the best model for the Indian population. The recommended focus is on agricultural training and government funding will be awarded through inspections and reports.

-

1860

Indian Affairs is transferred from the Imperial Government to the Province of Canada. This is afeter the Imperial Government shifts its policy from fostering the autonomy of native populations though industry to assimilating them through education.

-

1974

The aboriginal education system sees an increase in the number of native employees in the school system. Over 34 per cent of staff members have Indian status. This is after the government gives control of the Indian education program to band councils and Indian education committees.

-

1975

A provincial Task Force on the Educational Needs of Native Peoples hears recommendations from native representatives to increase language and cultural programs and improve funding for native control of education. Also, a Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development publication reports that 174 federal and 34 provincial schools offer language programs in 23 native languages.

-

1979

Only 15 residential schools are still operating in Canada. The Department of Indian Affairs evaluates and creates a series of iniciatives. Among them is a plan to make the school administration more culturally aware of the needs of aboriginal students.

-

1989

Non-aboriginal orphans at Mount Cashel Orphanage in Newfoundland make allegations of sexual abuse by Christian Brothers at the school. The case paves the way for litigation for residential schools victims.

-

1990

Phil Fontaine, leader of the Association of Manitoba Chiefs, meets with representatives of the Catholic Church. He demands that the church acknowledge the physical and sexual abuse suffered by students at residential schools.

-

1991

The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate offers an apology to Canada´s First Nations people.

-

1993

The Anglican Church offers an apology to Canada´s First Nations people.

-

1994

Th Presbyterian Church offers a confession to Canada´s First Nations people.

-

November 1996

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, or RCAP, issues its final report. One entire chapter is dedicated to residential schools. The 4,000-page document makes 440 recommendations calling for chancges in the relationship between aboriginals, non-aboriginals and govenrments in Canada. The Gordon Residential School, the last federally run facility, closes in Saskatchewan.

-

1997

Phil Fontaine is elected national chief of the Assembly of First nations, a political organization representing Canada´s aboriginal people.

-

January 7, 1998

The government unveils Gathering Strength: Canada´s Aboriginal Action PLan, a long-term, broad-based policy approach in response to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. It includes the Statement of Reconciliation: Learnung from the Past, in which the Government of Canada recognizes and apologizes to those who experienced physical and sexual abuse at Indian Residential schools and acknowledges its role in the development and administration of residential schools. St. Michael´s Indian Residential Schools, the last band-run school, closes. The United Church´s General Council Executive offers a second apology to the First Nations peoples of Canada for the abuse incurred at residential schools. The litigation list naming the Government of Canada and major Church denominations grows to 7,500.

-

2001

Canadian government begins negotiations with the Anglican, Catholic, United and Presbyterian churches to design a compensation plan. By October the government agrees to pay 70 per cent of settlement to former students with validated claims. By December, the Anglican Diocese of Cariboo in British Columbia declares bankruptcy, saying it can no longer pay claims related to residential school lawsuits.

-

December 12,2002

Presbyterian Church settles Indian residential schools compensation. It is the second of four churches involved in running Indian residenetial schools that has initialed an agreement-in-principle with the federal government to share compensation for former students claiming sexual and physical abuse.

-

March 11, 2003

Ralph Goodale, minister responsible for Indian residential schools resolution, and leaders of the Anglican Church from across Canada ratify an agreement to compensate victims with valid claims of sexual and physical abuse at Anglican-run residential schools. Together they agree the Canadian government wil pay 70 per cent of the compensation and the Anglican Church of Canada will pay 30 per cent, to a maximum of $25 million.

-

May 30, 2005

The federal government appoints the Honourable Frank lacobucci as the government´s representative to lead discussions toward fair and lasting resolition of the legacy of Indian residential schools.

-

October 21, 2005

The Supreme Court of Canada rules that the federal government cannot be held fully liable for damages suffered by students abused at a church-run school on Vancouver Island. The United Church carried out most of the day-to-day operations at Port Alberni Indian Residential School, where six aboriginal students claimed they were abused by a dormitory supervisor from the 1940s to the 1960s. The court ruled the church was responsiblefor 24 per cent of the liability.

-

November 23, 2005

Ottawa announces a $2-billion compensation package for aboriginal people who were forced to attend residential schools. Details of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement include an initial payout for each person who attended a residential school of $10,000, plus $3,000 per year. Approximately 86,000 people are eligible for compensation.

-

December 21, 2006

The $2-billion compensation package for aboriginal people who were forced to attend residential schools is approved by the Nunavut Court of Justice, the eighth of nine courts that must give it the nod before it goes ahead. (A court in the Northwest Territories is the last to give approval in January 2007.) However, the class-action deal – one of the most complicated in Canadian history – was effectively settled by Dec. 15, 2006, when documents were released that said the deal had been approved by seven courts: in Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Saskatchewan and the Yukon. The average payout is expected to be in the vicinity of $25,000. Those who suffered physical or sexual abuse may be entitled to settlements up to $275,000.

-

September 19, 2007

A landmark compensation deal for former residential school students comes into effect, ending what Assembly of First Nations Chief Phil Fountaine called a 150-year “journey of tears, hardship and pain – but also of tremendous struggle and accomplishment.” The federal government-approved agreement will provide nearly $2 billion to the former students who had attended 130 school. Indian Affairs Minister Chuck Strahl said he hoped the money would “close this sad chapter of history in Canada.”

-

April 28, 2008

Indian Affairs Minister Chuck Strahl announces that Justice Harry LaForme, a member of the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation in southern Ontario, will chair the commission that Ottawa promised as part of the settlement with former students of residential schools. At the ceremony, LaForme paid homeage to the estimated 90,000 living survivors of residential schools. “Your pain, your courage, your perseverance, and your profound commitment to truth made this commission reality,” he said.

-

June 11, 2008

Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologizes to former students of native residential schools, marking the first formal apology by a prime minister for the federally financed program.

-

October 20, 2008

Justice Harry LaForme resigns as chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for reidential schools. In a letter to Indian Affairs Minister Chuck Strahl, LA forme says the commission is on the verge of paralysis because the panel´s two commissioners, Claudette Dumont-Smith and Jane Brewin Morley, do not accept his authority and leadership.

-

November 5, 2008

Former Supreme Court of Canada justice Franck lacobucci, appointed in 2005 as the federal government´s representative to lead discussions toward a fair and lasting resolution of the legacy of Indian residential schools, agrees to madiate negotiations aimed at getting the Truth and Reconciliation Commission back on its feet.

-

January 30, 2009

Two of three commissioners on the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Claudette Dumont-Smith and Jane Brewin Morley, announce that they will step down effective June 1.

-

April 29, 2009

Pope Benedict XVI expresses “sorrow” to a delegation from Canada´s Assembly of First Nations for the abuse and “deplorable” tratment that aboriginal students suffered at Catholic church-run residential schools. Assembly of First Nations Leader Phil Fontaine says it doesn´t amount to an official apology but hopes it will “close the book” on the issue of apologies.

-

June 10, 2009

Indian Affairs Minister Chuck Strahl announces the appointment of Judge Murray Sinclair, an aboriginal justice from Manitoba, as chief commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for residential schools. Marie Wilson, a senior executive with the N.W.T Workers’ Safety and Compensation Commission, and Wilton Littlechild, Alberta regional chief for the Assembly regional chief for the Assembly of First Nations, are also appointed commissioners.

-

September 21, 2009

Justice Murray Sinclair says he’ll have to work hard to restore the commission´s credibility. Sinclair says people lost some faith in the commission after infighting forced the resignation of the former chairman and commissioners.

-

October 15, 2009

Gov. Gen. Michaëlle Jean relaunches the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission in an emotional ceremony at Rideau Hall. “When the present does not recognize wrongs of the past, the future takes its revenge,” Jean tells an audience that included residential school survivors. “For that reason, we must never, never turn away from the oportunity of confronting history together – the oportunity to right a historical wrong.”

-

December 30, 2009

Canada´s residential schools commission is settling in to its new home – and name – in Winnipeg. New chief commissioner Justice Murray Sinclair recently moved the headquarters of the commission from Ottawa to Winnipeg. The commission has also changed its name from the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission to the Truth and Reconciliation Canada (TRC).

-

March 2, 2010

Investigations into cases of students who died or went missing while attending Canada´s residential schools are a priority for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, says the group’s new research director.

-

March 19, 2010

Survivors of abuse at residential schools are fearing the end of federal funding on March 31 for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, a nationwide network of community-based healing initiatives. The federal government did not renew its funding for the foundation (AHF), which serves 134 community-based healing programs.

-

April 8, 2010

With the simple cutting of a ribbon, Canada´s Truth and Reconciliation Commission officially opens its headquarters in Winnipeg, two years after it was first created.

-

April 16, 2010

Thousands of aboriginal residential school survivors meet in Winnipeg for the first national event of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

-

June 21, 2010

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission is pleased with the outcome of its first national event in Winnipeg, despite receiving a smaller number of survivor statements than hoped.

-

November 12, 2010

The government of CAnada announces it will endorse the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, a non-binding document that describes the individual and collective rights of indigenous peoples around the world. The Truth and Reconciliation Committee hails the decision as a step towards making amends.

-

March 14, 2011

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission begins three months of hearing 19 northern communities in the lead up to its second national event, which will be held in Inuvik, N.W.T. between June 28 and July 1.

A number of factors laid the foundation for the creation of residential schools:

Racism and Superiority

The dominant European mentality and view of Canada’s original inhabitants was racist and backwards. The federal government considered it necessary to “assimilate” Indigenous people, and to have Indigenous nations conform to the European/Canadian customs, attitudes and ways of dressing, believing, behaving and working. Some politicians (and others) of the time sought to “kill the Indian in the child” and “civilize” Indigenous youth by separating them from their heritage and customs and indoctrinating them to European and Christian ways. This false, misguided and racist perspective denied and rejected the validity of First Nations languages, customs, spirituality and traditions. The main reason for these assimilationist policies was for land and resource exploitation. Dispossession and extinguishment of rights would also help to ensure the establishment of Canada as a legitimate nation state.

In 1876, the federal government introduced the Indian Act. Under the Act, the federal government took control of all aspects of the lives of First Nations people, including their means of governing themselves, their economies, religions, customs, traditions, land use and education. The Indian Act includes criteria and a definition of who is an “Indian.”

First Nations leaders supported education of their young. They recognized that providing their youth with the skills and knowledge relevant to the times would be important in the adaptation of their Nations and communities to the new situations arising from the presence of European settlers. However, the idea of separating children from their communities to attend school was not supported by parents and Elders.

First Nation leaders always insisted that schooling should be within, not distant from, their communities.

Treaties with First Nations obligated governments to fund the education of First Nations youth.

Residential schools were the federal government’s way of meeting their treaty commitments to education.

Indigenous people were considered to be a “problem” because their presence was getting in the way of the continuous expansion of settlement and exploitation by the European powers. Assimilation and absorption of Indigenous people into the “mainstream” were considered to help eliminate the “problem.

Christian missionaries considered it their duty to convert the First Nations to what they considered to be the only true religion, Christianity.

Map of residential schools recognized under the IRSSA

139 Residential Schools were recognized under the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement (IRSSA). Over 1500 institutions were not recognized under the terms of this agreement.